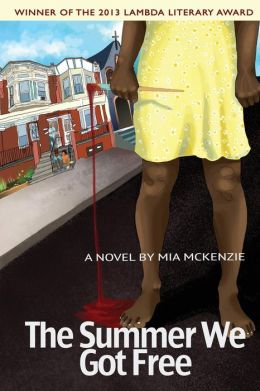

When it comes to finding queer fiction that’s also speculative, there’s something to be said for keeping up with awards and journalism devoted specifically to the LGBTQ end of the publishing world. That’s how I happened upon our next featured book in this year’s Extravaganza: The Summer We Got Free by Mia McKenzie. This novel, which I otherwise might not have encountered, was the winner of the 2013 Lambda Award for Debut Fiction—and a deserving winner it was.

The Summer We Got Free is a ghost story and a family drama, an intimate portrait of love and loss that also explores the complex dynamics of race and sexuality in America during latter half of the twentieth century. Oh, and if McKenzie’s name sounds familiar, that’s probably because she’s also the creator of the well-known site Black Girl Dangerous.

The book follows the trials of the Delaney family over the summer of 1976, when their son-in-law’s sister shows up unannounced one day to visit him on her way up to New York. Ava Delaney, who was once a vibrant young artist, has spent most of her adult life numb and colorless—but the arrival of this mysterious woman wakes something in her that she had forgotten was even possible. Plus, the family as a whole has been part of a seventeen-year neighborhood feud; their local pastor has it out for them, and on top of that, they’ve never recovered from the blow they were dealt when George Jr., Ava’s brother, was killed as a teenager.

All of that tension comes to a head, however, when Helena arrives—drawing up old hurts and asking new questions, provoking change left and right in the stagnant lives of the Delaneys.

First off, I’d like to say that I found The Summer We Got Free to be a damn good read—one that I think will be a pleasure for fans of sf and queer fiction both, though it hasn’t gotten much in the way of notice in speculative circles. The balance the novel strikes between the mundane and the uncanny is spot-on, for one thing. There’s the creaky old house, which seems to be a character of its own for most of the novel, and the literal and metaphorical ghosts it contains; there’s also the unquestioned magic of Helena’s arrival, the way that her presence appears to change things in the house like the fall of shadow in the corners and the temperature inside.

These eerie things, however, are paired with an in-depth family drama spanning more than two decades—marriages, deaths, losses, and feuds are the focal points of the story, all revolving around the violent loss of George Jr. one summer. The pairing of the supernatural with the realist in this novel gives it all a sense of immediacy and believability, too. There seems to be an undeniable truth in the ghosts that the characters begin to see—though they only see them once they’re working out their own memories of pain and loss, dealing with the trauma. So there’s also a psychological component to the hauntings that makes them seem, simultaneously, a touch unreal. It’s hard to say what’s literal and what isn’t, but I suspect we don’t need to and aren’t intended to.

One of the things I loved most about this book, though, wasn’t necessarily the ghost story—it was the story of Ava Delaney coming back to life after nearly twenty years of indifference, discovering again the taste of butter and the passion of desire, the ability to paint and to feel love. It’s a bittersweet story in some ways, since it necessitates her realization that she has never loved her husband, but it also opens up Ava’s life to new opportunities and avenues where she can be happy. (The epilogue, by the way, is a nice touch on this score: it’s good to see them get their happy endings, even if George doesn’t quite find his until his deathbed.)

George’s story, too, is moving—though less of a triumph, in the end. The generational gap between father and daughter and their ability to deal with their queerness, their place in a community, is clear: George cannot entirely overcome the trauma of his childhood or the pressure of religious denial, though he tries. His story also deals more with the complex interplay between masculinity, desire, and sexuality that informs his identity as a black man. It’s a conflict he doesn’t quite find a way out of, but is definitely well-illustrated and compelling.

Both are, in a sense, coming-out stories or “coming to terms” stories that deal with issues of identity and sexuality in the context of other lived experiences: heterosexual marriage, Christian religious community, and the different worlds of the American rural south and urban north, to name a few. These are difficult and layered personal narratives without simple solutions, and McKenzie does a wonderful job of illustrating them on the page.

Then there are also the changes that occur for Regina, the matriarch of the family, and Sarah, Ava’s sister. Her husband Paul, too, has a trauma to come to terms with: his murder of a young girl who he thought was assaulting his sister when they were teenagers. It’s sometimes hard to sympathize with Paul—he does, in the end, attack his sister and Ava—but he is also painted as a multifaceted individual with hopes and fears, with pain that drives him to act out. I think that’s an interesting maneuver, narratively, and one that I appreciate; it would be easy, in the close, to paint him as a villain, but McKenzie does not: he’s a man who is a part of a culture and a past that he has trouble separating himself from, and sometimes he’s not a good man, but he tries to be.

The Summer We Got Free is a first novel, though, and has a few of the hiccups I usually associate with them. Specifically, there are moments where the pacing is uneven—in particular during the climax, where the beats often seem to fall either too quickly or too slowly. However, as a whole it’s a remarkably well-wrought narrative, and I can absolutely see why it won the Lambda Award for Debut Fiction. I’m glad it did, too, so I had a chance to find it and pick it up.

Because I feel like it’s important, when writing about queer fiction and speculative fiction, not to forget the work of queer people of color—not to erase their contributions to the field and their willingness to share their own unique experiences of what it means to inhabit an LGBTQ identity in a world that is not only homophobic but racist as well. McKenzie’s novel is an excellent example of the power and importance of diverse stories: her work here spans the complexities of community and religion, gender and race, and offers a compelling narrative of the experiences of people like George and Ava. It’s full of personal and political history, the connections and experiences that make up a sense of self in the world.

As McKenzie says in her closing author’s note, the novel truly has a “pulse of family and community and womanhood and queerness”—a pulse that beats strong and sure throughout the text. Personally, I appreciated the novel’s intimacy and grounding in the experiential lives of its characters; I also appreciated McKenzie’s attention to detail, her careful rendering of the time and place that her novel takes place in. And all of these individual things also come together to form an engaging and moving story, one that offers each of its characters a chance at a fresh start after seventeen years—or more—of pain.

It’s good stuff, and I heartily recommend giving it a read.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.